Lesson Learnt

In a newly restored series of interviews, former Walker Art Center design curator Mickey Friedman revisits George Nelson, Charles Eames and Alexander Girard's unforgettable “Sample Lesson”.

Written by: Amber Bravo

© 2013 Eames Office LLC ( eamesoffice.com)

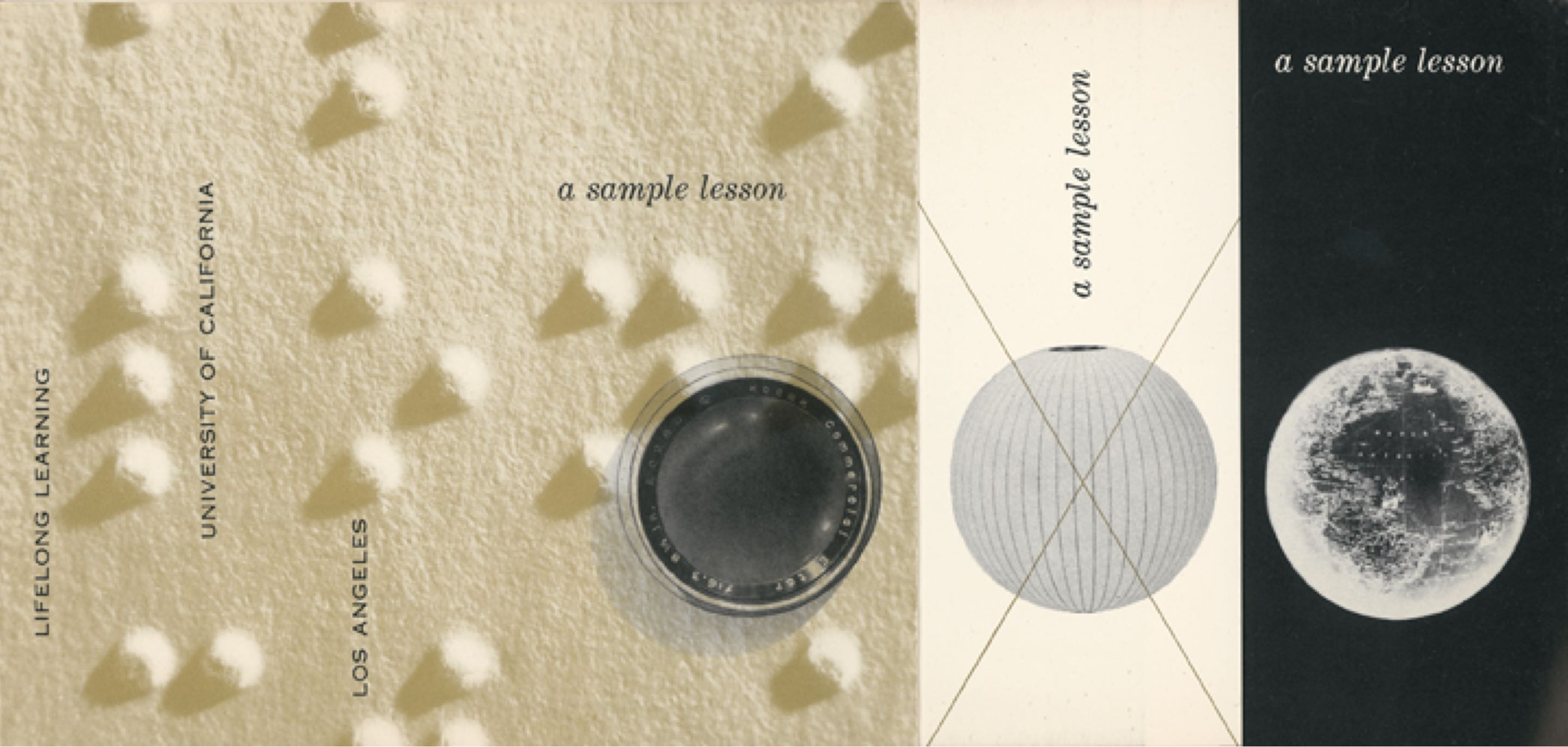

In spring 1952, George Nelson, Charles Eames and Alexander Girard took over a lecture hall at UCLA’s chemistry building to deliver the second instalment of a ready-made lecture, based loosely on the theme of “art as a kind of communication”. The Sample Lesson, as it’s commonly known today (Nelson called it “Art X”, Eames called it “A Rough Sketch of a Sample Lesson for a Hypothetical Course”), evolved out of a proposed arts education policy that Nelson initiated at the University of Georgia in Athens at the behest of Lamar Dodd, Chairman of the Department of Fine Arts.

Georgia’s programme, like most art curricula at the time, was drawn in the classical tradition: courses in theory, classes in drawing and painting, design, craft workshops for weaving, screen painting and ceramics. Nelson observed that while this type of instruction had obvious value, the training didn’t always address the realities of its students, many of whom were studying art out of a strong inclination or interest, and not for professional training. In “Art X = The Georgia Experiment”, a 1954 essay that Nelson penned for Industrial Design magazine and later republished in his book Problems of Design, Nelson asks, “Does it make sense for a girl whose main ambition is to become a homemaker to pretend for four years that she is aiming for a career in sculpture or painting? Perhaps it does, but isn’t the real problem to foster understanding and creative capacity so that these qualities could be employed in any situation? And if this were the real problem, how would a school go about solving it? Is intensive instruction in drawing and modelling the best way? Or is this method used simply because it has always been the art school method?”

© 2013 Eames Office LLC (eamesoffice.com)

As dated as his housewife example may be, Nelson’s rationale in developing a universally approachable and adaptable art curriculum – one that gets at the essence of a lesson creatively without frittering away unnecessary hours in a studio – was not. He advocated that by using mechanised aids such as slides, film and audio, the learning experience could be expedited and augmented. “It was perfectly clear that much time was being wasted through methods originally developed for other purposes,” he explains. “For example, one class was finishing a two-week exercise demonstrating that a given colour is not a fixed quantity to the eye but appears to change according to the colours around it. In a physics class, such a point would have been made in about five minutes with a simple apparatus, and just as effectively.”

The faculty responded positively to Nelson’s ideas, and he was invited to form a small advisory committee and return with a more detailed proposal. He recruited Charles Eames to craft another presentation that further refined and expanded the initial line of thinking. This time, however, their progressive ideas were met with hostility and confusion. The faculty felt threatened by the idea of being replaced by machines, and that performance might be evaluated in quantifiable terms. “That night Eames and I discussed the turmoil created by what we had believed were innocuous proposals,” Nelson recalls. “It was our feeling that the most important thing to communicate to undergraduates was an awareness of relationships.” So they decided to put the proof in the pudding and lead by example: They would create a sample lesson. Recruiting Girard to the team, they set about creating their curriculum.

More a multimedia extravaganza than a lecture, the team used film, slides, sound, music, narration and even smell to elucidate their subject. According to Charles, The Eames Office had already been working on their film A Communications Primer, from which they borrowed several image sequences and which largely determined the subject of the Sample Lesson. (Nelson does not corroborate this story.) When the group came together to present their lecture, Nelson recalls, “It was as if we’d been sitting in the same room for weeks and months because everything fitted. Even allusions Eames would make would fit with allusions we would make. It was an extraordinary moment.” Nelson paints a vivid portrait of how the lesson played out in his 1954 essay:

A slide goes on the screen, showing a still life by Picasso. A narrator’s voice identifies it, adding that it is a type of painting known as "abstract", which is correct in the dictionary sense of the word since the painter abstracted from the data in front of him only what he wanted and arranged it as he saw fit. The next slide shows a section of London. The dry voice identifies this as an abstraction too, since out of all possible data about this area, only the street pattern was selected. The camera closes in on the maps until only a few bright colour patches show… then a shift to a distant view of Notre Dame, followed by a series, which takes you closer and closer. The narrator cites the cathedral as an abstraction – the result of a filtering-out process… the single-slide sequence becomes a triple-slide projection. Organ music crashes in as the narration stops. The interior becomes a close-up of a stained glass window. Incense drifts into the auditorium. The entire space dissolves into sound, space and colour.